This ambrotype was created through a similar process to a daguerreotype although an ambrotype produced a negative image that became visible when the glass plate was backed by dark material. This particular ambrotype is of Nicholas Wesley Miller and his bride, Sadie Little Miller. Their marriage was recorded in Harris County on August 21, 1860. Mr. Miller was wounded in the Battle of Hatcher’s Run near Petersburg, Virginia on February 6, 1865 and succumbed to the injury on June 5 of that year. TCA Collections

In our modern world that includes smartphones, a day hardly passes without us snap-ping a “photograph.” Selfies, family portraits, school picture day, tabloid journalism – photography has become so ingrained in our culture, it is difficult to fathom that it is a relatively new concept. Less than two hundred years ago, a portrait had to be painstakingly, and expensively, painted for one’s image to live into perpetuity and it was not an exact image, but rather, the artist’s vision of the scene.

The idea of rendering a subject’s exact likeness onto paper really came into focus (pun intended) when Johannes Kepler coined the term “photograph” for a drawing made with the light from his telescopic optics in 1604. Kepler and other astronomers wanted to make the paper itself sensitive to light and in 1717, Johann Heinrich Schulze used a solution of silver nitrate that darkened when exposed to light to catch an image of the stars, but it did not stop darkening. One hundred and ten years later, in 1827, French inventor, Nicéphore Niépce, used a sheet of metal covered in a film of chemicals to capture what is considered to be the first photograph. It took eight hours for the image to etch into the sheet, but it was the beginning of rapid development.

Children Sleeping on Mulberry Street by Jacob Riis, c. 1890, courtesy Museum of the City of New York.

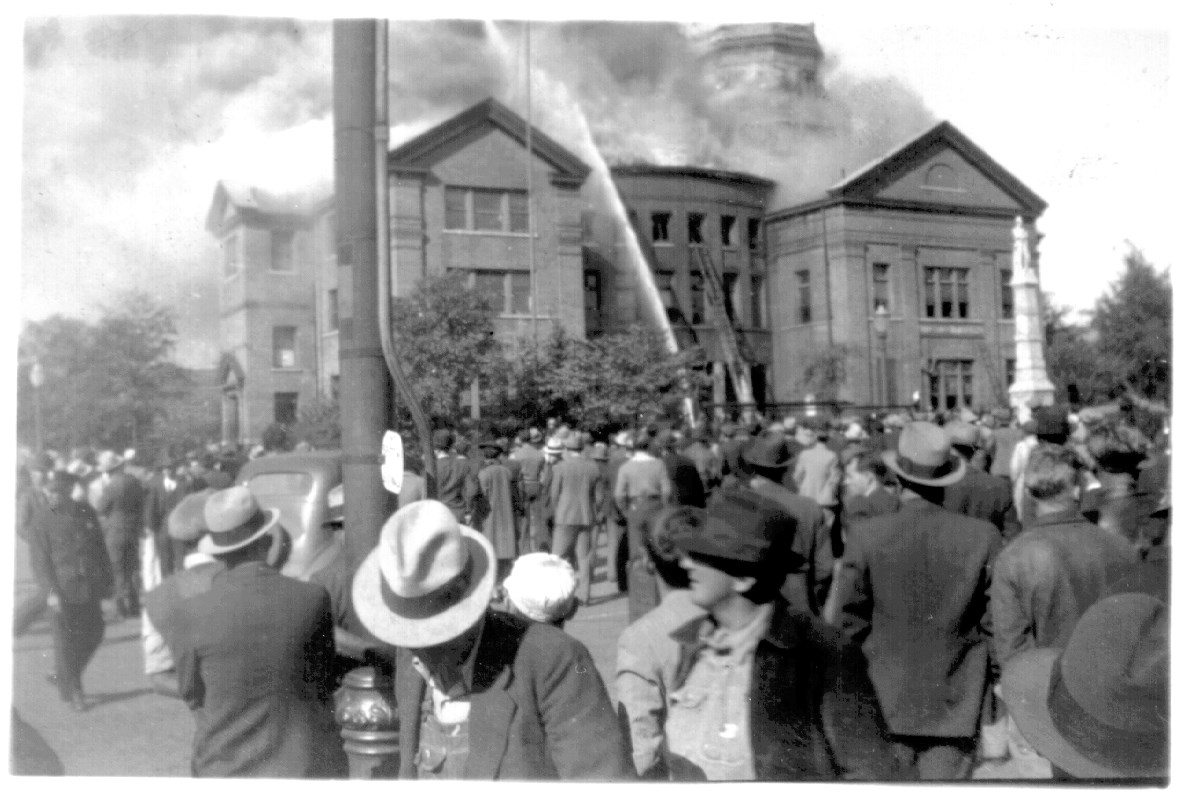

Louis Daguerre built on Niépce’s formula when he ex-posed a thin silver-plated copper sheet to the vapor produced by iodine crystals. The product was a light-sensitive silver iodide surface that could be “developed” into a visible image. While still messy, expensive, time-consuming, and somewhat dangerous given the chemicals involved, the Daguerreotype brought photography to the masses in 1839. This process dramatically changed how we consider history – his process provided the first photographic images of an American president. John Quincy Adams posed for the photograph in 1843, fourteen years after leaving office in 1829. In a single generation, imagery of war went from the romanticized sketches, drawings, and paintings of the Revolution, to the shockingly realistic glass plate photographs of the Civil War. No longer was imagery confined to grandiose battle scenes depicting gentleman generals rushing the fields. With the clunky collodion plates and mo-bile darkrooms in tents and wagons, photographers like Alexander Gardner, Timothy O’Sullivan, and Mathew Brady sent images of actual carnage to news publications. This stark contrast of documentation led Mathew Brady to conclude that “the camera is the eye of history.”

Taken by Alexander Gardner after the Battle of Antietam or Sharpsburg in Maryland in September 1862. Courtesy Library of Congress

That eye was not only focused on war, but also on the common man and woman. The daguerreotype proved popular amongst the middle class’ demand for portraiture. In 1884, George Eastman, of Rochester, New York, developed dry gel on paper. The “film,” as he called it, replaced the photographic plate so there was no longer a need to lug around large crates of plates and toxic chemicals. In July 1888, Eastman’s Kodak camera hit the markets under the slogan “you press the button, we do the rest.” By 1887, German innovations of Adolf Miethe, combined magnesium with potassium chlorate to make flash powder. With flash photography, social reformers like Jacob Riis, an immigrant himself, captured the conditions in some of the impoverished, and often dark, areas of New York City. Photojournalist, Riis’s works introduced the harsh lives of the working class to the gentry.

The work of Riis, Brady, and others, ushered in what might be called a “golden age” of photojournalism were it not for the genre’s focus on human suffering. Lewis Hine studied sociology and taught the subject in New York, where he used photography as an educational medium. By 1908, he realized that medium could be used to enact social reform and began taking pictures of child laborers. The National Child Labor Commit-tee used Hine’s images to enact a significant change in legislation and reducing child labor. A successful portrait photographer in San Francisco during the 1920s, by 1933, Dorothea Lange began taking pictures of the unemployed in the height of the Great Depression. It was Lange’s now-famous images of migrant workers and breadlines that encouraged photographic documentation across the country and the world. As the Depression wore on, other photographers emerged, and through projects funded by federal administrations, history has realistic documentation of tenant farmers in Alabama, Atlanta mechanics, Civil Conservation Corps workers in Warm Springs, everyday life across the south that would not otherwise exist.

Sadie Phifer, A Cotton Mill Spinner in Lancaster, SC, 1908, by Lewis Hine, courtesy Library of Congress

Today, because of these pioneering photographers, those left at home saw the horrors of Iwo Jima and D-Day, and also the joy of V-J Day. Because of photography, we have witnessed protest in the city down the road and across the globe. Through imagery, we have been called to action during crisis, and celebrated with our global neighbors.

If the camera really is the eye of history, we must take advantage of what most of us carry in our pockets or purses. What may seem like everyday events will be considered history in the future. All of us have the potential to be our own Mathew Brady, Jacob Riis, or Dorothea Lange. Their photos helped change the world and capture a moment frozen in history. What can your photos do? – Shannon Gavin Johnson