Rutledge Thomas Blasengame Parham resided only briefly in Troup County, but he is a key figure in one of our most enduring legends. We think he arrived here in late summer of 1864, as a patient in one of the Confederate hospitals located in LaGrange. The twenty-year-old captain grew up in Mobile, where his father was a customs inspector. He was well educated, articulate, and a talented musician. Cultured young officers were a rare commodity in war-time LaGrange. He soon moved from the hospital ward to a private home to continue his convalescence, enjoying attentive care from the local ladies.

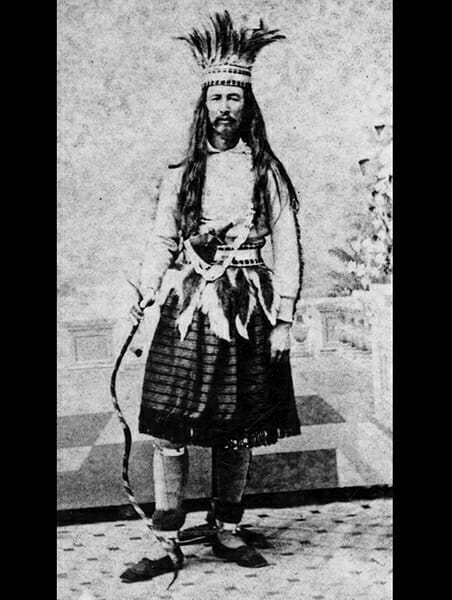

Joe Cain, pictured here as Chief Slacabamorinico, became known as the “Father of Mardi Gras” in Mobile.

Parham came to the attention of General R.C. Tyler, commandant of the garrison at West Point, and as his condition improved, he became Tyler’s adjutant. Captain Parham served in that capacity until April 16, 1865, when Colonel Oscar H. Lagrange’s brigade of Federal cavalry attacked West Point, aiming to seize the vital Chattahoochee River bridges. General Tyler was killed defending the fort that bore his name. After a day-long struggle, Colonel James Fannin, who succeeded Tyler in command, surrendered the fort. It was Rutledge Parham, acting on Fannin’s orders, who tied his handkerchief to a ramrod and waved it over the parapet. Parham and about sixty others became prisoners of war. The next day, April 17th , Confederate officers rode alongside their Federal counterparts as the column marched from West Point to LaGrange. About five P.M., Mayor J.A. Long and a delegation of city officials met the column and surrendered the town to Colonel Lagrange. In a magnanimous gesture, Colonel Lagrange paroled Fannin and other Confederate officers so that they could spend time with their families. Mrs. Sarah Pullen and her daughter Leila, two of Parham’s former nurses, invited the Captain and two Federal officers to dine with them that evening.

More than thirty years later, on December 17, 1896, Leila Pullen (Mrs. Charles Morris) recounted the incident in an address to the United Daughters of the Confederacy in Atlanta. The story, romanticized and embellished, was published in the November 1904, edition of Ladies Home Journal, and that was the genesis of the Nancy Harts legend.

Rutledge Parham returned to his home in Mobile after the

war, and found employment as a clerk for various businesses. He became active in the Tea Drinker’s Society and other fraternal organizations. Parham joined Joseph Stillwell Cain and other friends to form “The Lost Cause Minstrels.” Mobile’s long tradition of parades and revelry (usually on New Year’s Eve) was interrupted by the war. In 1867, the Minstrels decided to revive the tradition. On Fat Tuesday the Minstrels dressed in outrageous costumes and paraded through Mobile on a coal wagon, entertaining crowds with loud music and pantomime. The tradition continues to this day. Joe Cain, pictured here as Chief Slacabamorinico, became known as the “Father of Mardi Gras” in Mobile. Rutledge Parham slipped into obscurity. His name appears on census records and city directories as late as 1883, but after that we find no record of him; no newspaper accounts, no obituary, no grave location.