Many of the foods featured in our latest exhibit, Gather ‘Round the Table: Troup County’s Culinary History, became Southern favorites after long and convoluted journeys from exotic origins. That is not the case with pecans.

A colorized photograph of a praliniere sitting in Jackson Square in New Orleans, 1929. Image courtesy Louisiana Historical Society

Pecans are indigenous to the lower Mississippi Valley, primarily eastern Texas and Louisiana, but by the time of European colonization, Native Americans had spread pecan trees over much of the Southeast. Pecans are one of our more recently domesticated crops. Both Thomas Jefferson at Monticello and George Washington at Mount Vernon planted pecans, which they called Illinois nuts, but commercial pecan production only began around 1880 when grafting techniques were improved. Before that time, almost all pecans consumed in the U.S. were collected from wild trees. In 1833, newlyweds Joel D. and Mary Middlebrooks Newsom started construction of a magnificent Greek Revival style home which at that time was about five miles from LaGrange on the Big Springs Road. The estate became known as Nutwood because of the tradition that the first pecan tree planted in Troup County grew on the place. Fifty years later, o

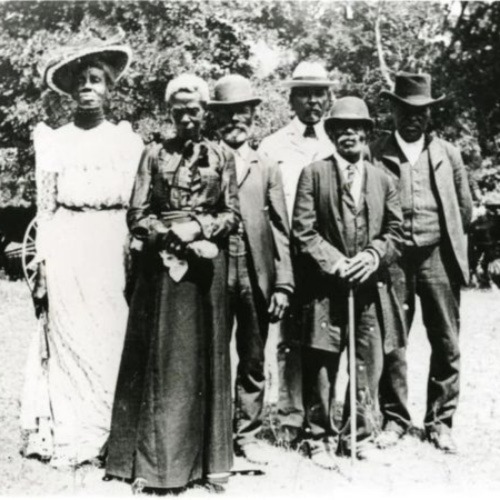

n August 23, 1883, the editor of the LaGrange Reporter lamented that there were only two known pecan trees in Troup County, and he urged his readers to plant more. Almost as early, the pecan was featured in cookbooks. In 1824, Mary Randolph offered a recipe for a milk-based pecan custard in her cookbook, The Virginia Housewife, and in 1896, Harper’s Bazaar published a similar recipe. Some early Texas recipes called for molasses as the custard base, but it wasn’t until the 1920s, when the makers of Karo Syrup printed a simple recipe on their label that pecan pie soured in popularity. Other delicacies made from the nut were popular very early in American history. For example, pralines, the delicious concoction of pecans, sugar, butter, and cream, were first created in France and brought with Ursuline Nuns to New Orleans in 1727. The nuns were chaperoning a group of “casket girls” or young women from orphanages and convent schools that the French government sent as potential brides for colonists. The girls carried everything they owned in a small trunk called a casket, and nuns accompanied them to instruct them in domestic duties and to ensure their virtue. As the casket girls married and spread across southern Louisiana they combined their training with local traditions to create the foundation of creole cooking. One of their adaptations was substituting locally available pecans for almonds and adding butter and cream to the recipe for Praslin’s candy. By the mid-nineteenth century pralines were so popular in New Orleans that “Pralinieres,” mostly women of color, supported themselves selling candy on street corners in the French Quarter. As for the nut’s pronunciation: the word comes from the French pacane, which, in turn, is borrowed from the Algonquin Indian word, pakani, meaning large, or hard nut. If you grew up in New Orleans or along the Gulf Coast it is likely pronounced pa-kahn; elsewhere in the South, and here in Troup County, the delicious nut is probably pronounced pee-can. — Randy Allen

Modern image of Nutwood, the home of Joel D. and Mary Middlebrooks Newsom. Image courtesy of Nutwood.