With masks over their faces, members of the American Red Cross remove a victim of the Spanish Flu from a home in St. Louis, MO, one of the first cities struck by the virus. Courtesy St. Louis Dispatch.

Illnesses have plagued humanity since the earliest days. Communicable diseases existed during humankind’s hunter-gatherer days, but as we shifted to an agrarian lifestyle and settled into communities, germs were passed more easily. The more civilized humans became, constructing cities and building trade routes between them, widespread epidemics grew. Malaria, tuberculosis, leprosy, influenza, smallpox, and many others first appeared during this early era.

The earliest recorded pandemic occurred during the Peloponnesian War.

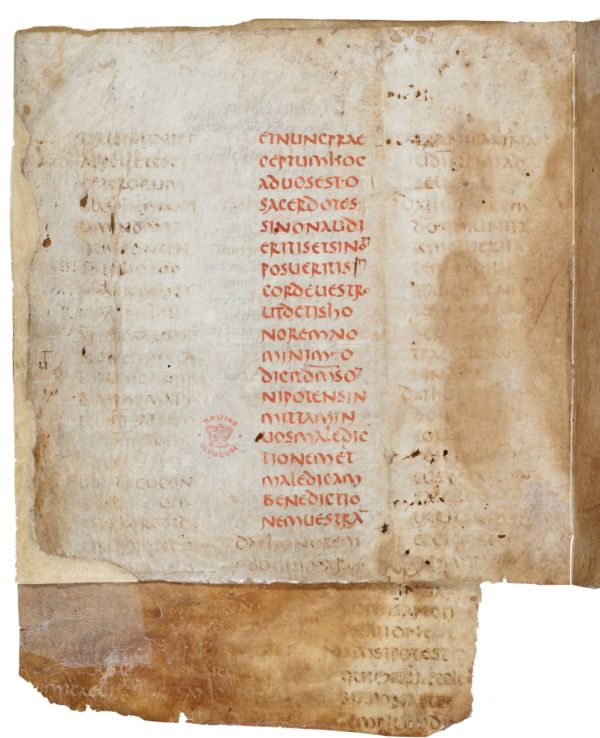

These fragments are all that survive from a book written in North Africa in the late fourth century. They preserve part of a collections of letters written by Cyprian, bishop of Carthage. The letters were copied using a format of four narrow columns of text per page with Biblical quotes written in red ink to attract the eye. Images courtesy the British Library.

The two most powerful city-states in ancient Greece, Athens, and Sparta, were at war between 431 and 404 B.C. Just a year after war began, the sickness, like-ly typhoid fever, passed through Libya, Ethiopia, and Egypt before reaching Greece. Thucydides’ records indicate that some two-thirds of the population died from the disease, drastically reducing Athenian soldiers and ultimately ending the Golden Age of Greece.

Then came the Antonine Plague in 165 A.D. which was probably the first appearance of smallpox. It began with the nomadic Huns who passed it to Germans, who passed it to Romans, who spread it throughout the Roman empire. We remember the Roman Empire as a conduit of trade, but those trade routes carried as many germs as goods.

Less than a century later, the Cyprian Plague began in 250 A.D. It was named after its first known victim, Cyprian the Bishop of Carthage, who vividly documented the disease in a sermon on mortality. There were recurring outbreaks over the next three hundred years and in 444 A.D., it afflicted Britain so badly that their defenses against the Picts and Scots failed. This caused the British to seek help. The Saxons, Angles, and Jutes came from what is now Denmark and Germany and brought with them a new language. Indeed, in an indirect manner, the Cyprian Plague is responsible for the British speaking English, and by extension Americans speaking English.

Generally regarded as the first recorded incident of the Bubonic Plague, the Plague of Justinian struck between 541 and 542 A.D. John of Ephesus recorded a detailed description of the plague and its effects in Pales-tine and Constantinople. As a Christian writer, John clearly stated that the end of the world was at hand; to him, the plague was a manifestation of divine wrath and a call for repentance. Passed through the Byzantine Empire and Mediterranean port cities, John wrote that many ships would float aimlessly at sea, later washing up to shore with all of their crew dead from plague. His account vividly detailed scenes of havoc in which men collapsed in agony in the public squares. The fear of being left unburied, or of falling prey to scavengers, led many individuals to wear identification tags and to avoid leaving their homes.

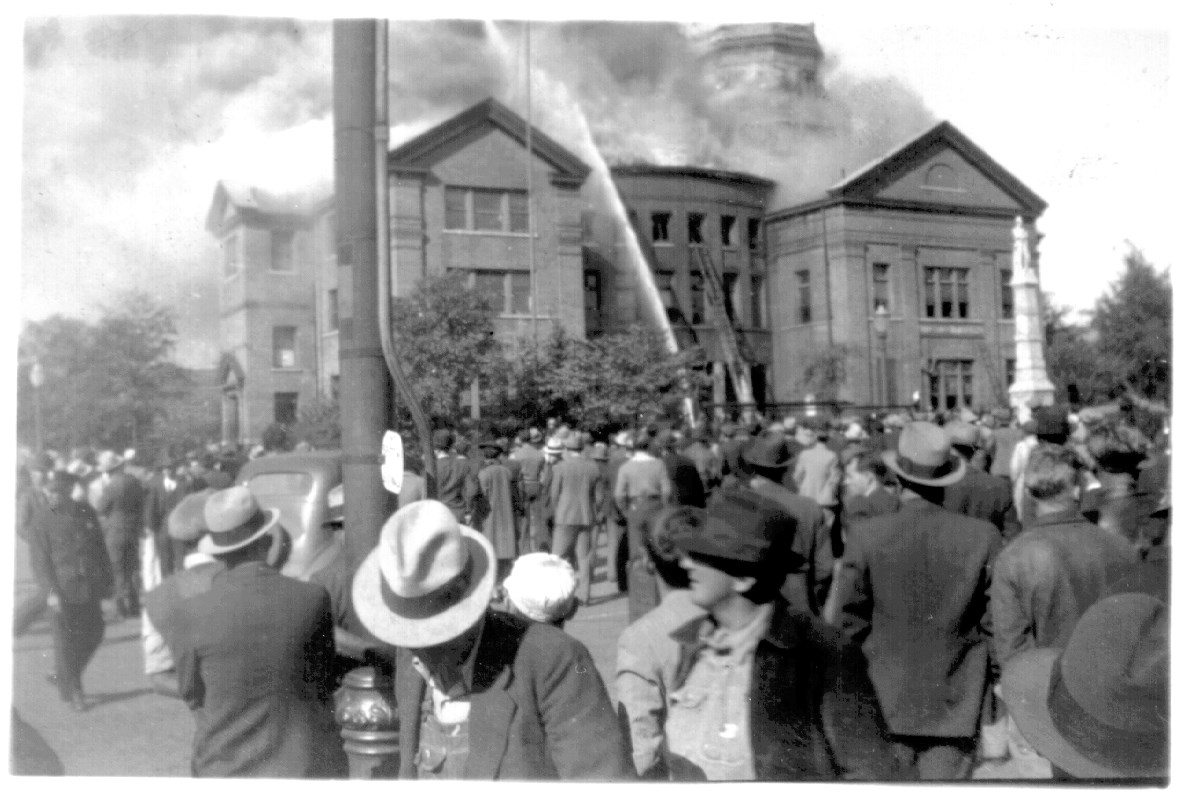

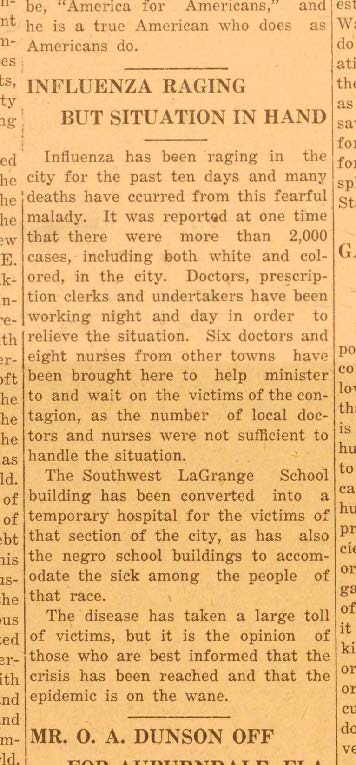

This article ran on the front page of The LaGrange Graphic on Noveember 14, 1918. While the “situation was in hand,” a week earlier the City had already begun requiring open-air funerals only. TCA Collections.

While staggering, the death toll from the disease itself was not the only impact. The urban poor were the first to suffer from the devastating effects, but the pestilence soon spread to the wealthier districts. In some rural areas, the plague reached the farmlands after the planting, and the crops ripened with no one to harvest them. Bread became scarce, and some of the sick may actually have died of starvation, rather than disease. Many houses became tombs, as whole families died from the plague without anyone from the outside world even knowing.

The twenty-five million that died during the Justinian Plague pales in comparison to the Black Death. From 1346 to 1353, the outbreak ravaged Europe, Africa, and Asia with an estimated death toll between seventy-five and two hundred million people. It arrived in Europe in October 1347, when twelve ships from the Black Sea docked at the Sicilian port of Messina. Those awaiting the ships at the docks were horrified to find that most of the sailors aboard the ships were dead, and those still alive were gravely ill and covered in black boils. Sicilian authorities immediately ordered the “death ships” back out into the harbor, but it was too late. Today, scientists know that the bacillus that causes the Black Death is transferred from person to person pneumatically, or through the air, as well as through the bite of an infected flea or rat. Both fleas and rats were easily found almost everywhere in medieval Europe, but they were particularly prevalent aboard ships, which is how the disease spread so quickly. After Messina, the Black Death spread to the port of Marseilles in France and Tunis in North Africa. Through Rome and Florence, it hit trade routes and by the middle of 1348 had reached Paris, Bordeaux, Lyon, and London.

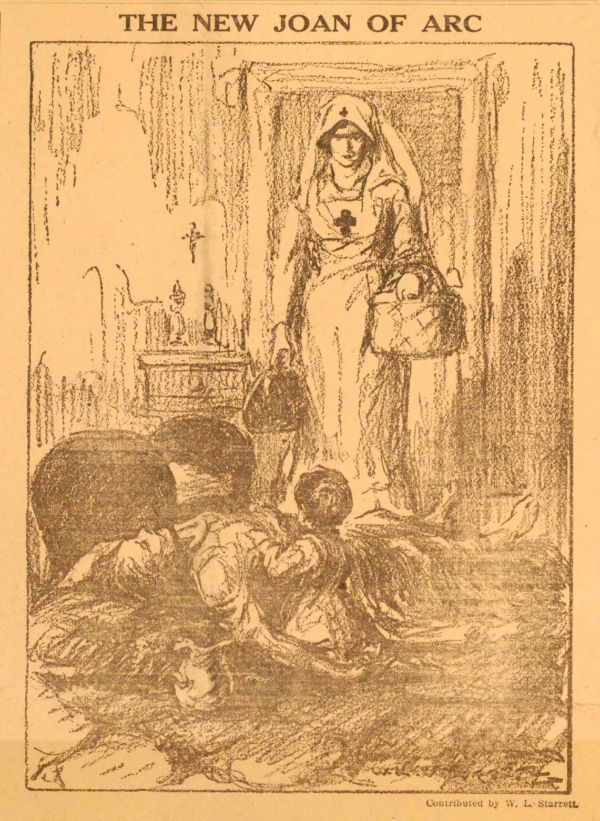

This image by W. L. Starrett ran in newspapers across the country in 1918, including our local LaGrange Graphic. TCA Collections.

The Black Death epidemic had run its course by the 1350s, but the plague reappeared every few generations for centuries. It is from this particular outbreak that we first find documentation of the Plague Doctor. The Renaissance brought forth a new enlightened age, but the advances were slow in the medical world. The costume that is so synonymous with the plague, with its eerie beak-like mask and black waxed fabric overcoat, was created by Charles De L’Orme in 1630 to protect the practitioner against the illness. The mask’s nose was often stuffed with aromatics like juniper berries, mint, camphor, cloves, and laudanum.

While sickness certainly happened, our little corner of the world, here in Troup County, has no record of such an epidemic before the Spanish Flu of 1918. During the thick of World War I, a pandemic of what is now known as H1N1 or Swine Flu hit. To maintain morale, wartime censors in the U.S., England, Germany, and France minimized early reports of illness and mortality. The papers were free to report the epidemic’s effects in neutral Spain which created a false impression that Spain experienced a higher rate of the disease – hence the name “The Spanish Flu.” The first wave occurred in the Spring of 1918. It was generally mild with people usually recovering after several days. But the second wave in Fall of 1918 and was highly contagious, often killing victims within hours or days of their developing symptoms. Typically, influenza outbreaks most often affect juveniles, the elderly, or already weakened patients, but this strain predominantly killed previously healthy young adults. The war left parts of the world with a shortage of healthcare workers, making conditions even worse. The Spanish Flu killed at least 20 million people in 18 months, though some estimates put that figure at closer to 50 million, including 675,000 Americans. Some communities were so severely affected that healthcare workers could not tend to the sick, nor could the grave-diggers bury the dead because they too were ill. In some areas, mass graves had to be dug with steam shovels, and bodies buried without coffins.

In Troup County, more than 2000 cases were reported. As a preventative measure to stop the spread of the disease, the Board of Health prohibited public gatherings including schools, funeral homes, and churches. Six doctors and eight nurses from other Georgia counties came to Troup County to assist. Two local school buildings were converted into temporary hospitals. The community even established an emergency fund to cover the expenses accrued during the pandemic, raising over $7500 in four hours. They were heroic measures, but for some 270 local residents, it was too little, too late.

This barely considers the vast history of widespread illness. Other pandemics include variations of flu, smallpox, yellow fever, SARS, Ebola, and MERS. The impact of disease has, on more than one occasion, altered history and we have learned from each instance. While pandemics are likely to continue to play a role in human life, much as we have seen with the recent quarantine for Covid-19, it is through this history that we will be better prepared for our future.

–Shannon Gavin Johnson