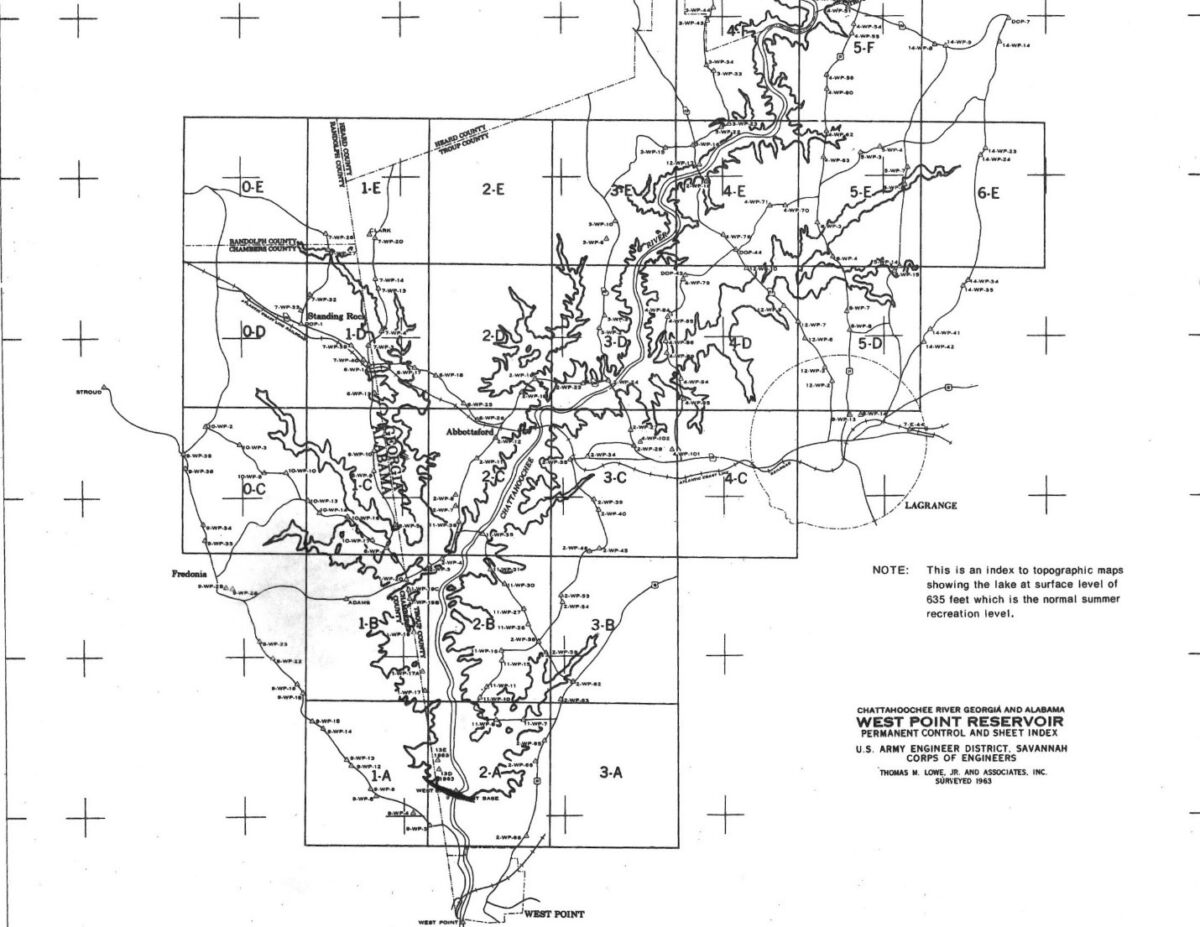

My earliest recollection of anything to do with West Point Lake was sometime in the early 1960s. I don’t remember the exact date, but it was a Sunday afternoon and my grandmother’s neighbors were gathered around her dining room table looking at a big topographical map. My cousin worked for the City of LaGrange and had managed to get copies of the Corps of Engineers maps showing the proposed high water line for the impoundment of West Point Dam. The mood was somber. Everybody examined the topo maps with one question in mind. Would the backwater get their place? Fred and Mozelle Alewine’s farm was across the road from my grandmother, where View Pointe subdivision is now. Mr. Fred expressed paradoxical optimism. “Those fools that built their town in the flood plain have been talking about a dam since I was a boy. I don’t believe I’ll ever live to see it.” He was right, in one sense. As early as the 1920s business interests in West Point and the Valley had advocated construction of a flood control dam above their town.

“Those fools that built their town in the flood plain have been talking about a dam since I was a boy. I don’t believe I’ll ever live to see it.” He was right, in one sense. As early as the 1920s business interests in West Point and the Valley had advocated construction of a flood control dam above their town.

“What can we do?” Somebody vocalized the question on everyone’s minds.

“Not a damn thing.” It was the only profanity I ever heard my grandmother utter. “It’s the government,” she said, “and you cain’t fight Uncle Sam.”

My grandparents’ little farm was on the west side of U.S. 27 where it crosses Beech Creek. My family, like a lot of other folks in the area, joked that they worked in the cotton mill to support their farming habit. During the first quarter of the twentieth century, the boll weevil, fluctuating cotton prices, and drought had forced them to give up farming for the relative security of jobs in the textile industry. Though they endured it for twenty-five years, or more, they never really adapted to life in the mill village, so when the economy rebounded with World War II they bought a few acres north of LaGrange. The days of small scale cotton farming were gone but they planted a small orchard, kept a few pigs and cows, and grew corn on the bottom land along Beech Creek. They were hardscrabble folks who had lived through two world wars and the Great Depression. They were accustomed to hard times and bitter disappointment. I never knew my grandfather, who died when I was a year old, but my grandmother was the sort who believed that life was to be endured rather than enjoyed.

For more perspective on the political and cultural ramifications of the West Point Dam project, I recommend The Urban Appropriation of the Rural South: The West Point Dam and the Politics of Outdoor Recreation, by Henry Jacobs. In his senior research project, Jacobs looks at how population and power had shifted from rural to urban America. He examines the motives and agendas of the Federal Government, local leaders, and the land owners. Focusing on our region, in particular, he explains how proponents of the dam were finally able to sell their vision by touting the multipurpose aspects of the project. In addition to their original goal of flood control, they emphasized hydro-electric power, recreation, and economic opportunities that would benefit the region’s growing metropolitan areas. Some enthusiasts even suggested that a system of dams and locks would link Atlanta to the Gulf. The concept of multiuse, benefiting a large segment of the population, made the project cost effective for the government, and that’s what finally got the dam built. I feel kind of old when I realize that I lived through the events that Henry Jacobs researched as a history project. My experience was that rural Troup Countians viewed “that damn project,” as they called it, as yet another manifestation of the Federal Government overstepping its authority. Many of them had benefitted from New Deal programs during the Great Depression but they were nonetheless wary of a government that was pushing daylight saving time, and a bunch of Yankee holidays, and worst of all, integration, down their throats. Now the government threatened to take their land for a project that offered them nothing in return. As I remember it, almost all the resentment was focused on the government, and not on the local business and civic leaders who were the real promoters of the dam project. The movers and shakers in West Point and LaGrange were happy to allow the Corps of Engineers to be the bad guys, while they were the ones who stood to reap the financial reward.

The folks gathered at my grandma’s that Sunday afternoon discussed pooling resources to hire a lawyer, but the consensus was that the lawyers would take their money and they would still lose their land. It’s been sixty years, but I still remember the palpable sense of hopelessness and resentment as they filed out of that meeting. And, I remember that Mr. Alewine, as he was leaving, turned and said, “Joe Young told me they weren’t going to take his land without a fight.”

If Joe Young had been a man of lesser means, I suspect his neighbors and acquaintances would have called him a crazy old coot. As it was, they deemed him eccentric. In his later years, when I knew him, he drove a big white International Harvester Travelall filled with tools, and saddles, and hay bales, and occasionally, a baby calf. One time, I came upon that Travelall parked on the side of the road, actually sticking out into the road, and Mr. Joe walking down the ditch. I stopped to ask if everything was alright. He held up a Coke bottle and said, “Mr. Cottle, up there at the store, gives me three cents, cash money, for every one of these things I bring in.” Mr. Joe probably owned more Coca Cola stock than George Cobb, but he wasn’t about to let three cents, cash money, go unclaimed.

Joseph Lauderdale Young was born April 17, 1905. — Now this is the place where it’s easy to fall into the trap that has been called “those boring begats.” You know, Abraham begat Isaac, and Isaac begat Jacob, and so on. I can sum up this story by saying that Robert Young, Sr. begat Robert Young, Jr., who begat Joe Young, who didn’t begat anybody, and that’s how the Georgia Sheriff’s Youth Home ended up with Pineland. — At the risk of boring you further, I have to include a little bit of family history to complete the story.  Joe’s grandfather, Robert Madison Young, Sr. was enumerated in the 1850 census for Rockingham County, North Carolina, but by 1856, he resided in Troup County where he married Mary Eaton Yancey. Over the next couple of years, Robert purchased more than a thousand acres of land along Yellow Jacket Creek and Shoal Creek. Mary died in 1858, and in 1861, Robert married a young widow, Susan Pitts. He evidently came through the Civil War unscathed, physically and financially, because in 1868, he purchased six hundred additional acres, including the mill site on Beech Creek. A Troup County Inferior Court record from 1834 refers to John Bird’s Mill, so we think that he built the first mill on the site. John’s widow, Amanda, received a life interest in the property when he died in 1853, and Robert Young, Sr. purchased the property when she died in 1868. When Robert died in 1878, title to the property passed to his widow, Susan and their four children. In 1897, Robert Young, Jr. purchased the property from his mother and siblings, putting it in the name of his wife, Lottie Guinn Young. Robert and Lottie Young were Joe’s parents. In 1959, when their mother died, Joe bought out his brothers’ interest in the property.

Joe’s grandfather, Robert Madison Young, Sr. was enumerated in the 1850 census for Rockingham County, North Carolina, but by 1856, he resided in Troup County where he married Mary Eaton Yancey. Over the next couple of years, Robert purchased more than a thousand acres of land along Yellow Jacket Creek and Shoal Creek. Mary died in 1858, and in 1861, Robert married a young widow, Susan Pitts. He evidently came through the Civil War unscathed, physically and financially, because in 1868, he purchased six hundred additional acres, including the mill site on Beech Creek. A Troup County Inferior Court record from 1834 refers to John Bird’s Mill, so we think that he built the first mill on the site. John’s widow, Amanda, received a life interest in the property when he died in 1853, and Robert Young, Sr. purchased the property when she died in 1868. When Robert died in 1878, title to the property passed to his widow, Susan and their four children. In 1897, Robert Young, Jr. purchased the property from his mother and siblings, putting it in the name of his wife, Lottie Guinn Young. Robert and Lottie Young were Joe’s parents. In 1959, when their mother died, Joe bought out his brothers’ interest in the property.

Around 1875, Robert Young, Sr. made improvements to the grist mill and built a saw mill, pictured here, on the north side of Beech Creek.

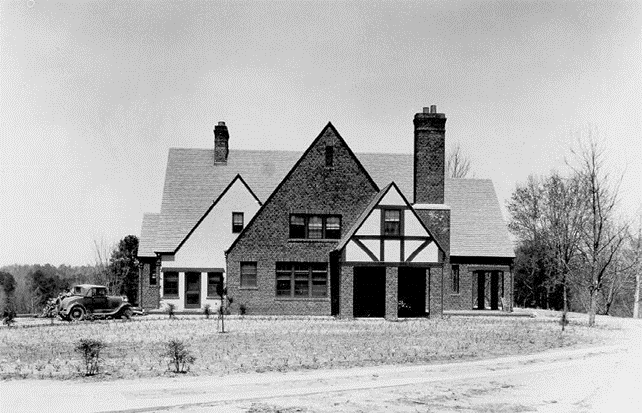

None of the Youngs were millers. They always employed others to run the mill. In fact, they were at times absentee landlords. Through the late 1800s and into the twentieth century the Young family at times resided in the old Bird home on the property and at other times they lived on Hill Street in LaGrange. In 1929, Robert Young, Jr. razed the old Bird place and constructed the brick Tudor style house that still stands, on the west side of Young’s Mill Road, just south of the mill site. The mill, too, underwent significant changes during the hundred and forty years it existed.

This house, built by Robert and Lottie Guinn Young in 1929, replaced the old John Bird home. The house, which was designed by architect and builder Tom Hutchinson, still stands on Young’s Mill Road, just south of Beech Creek.

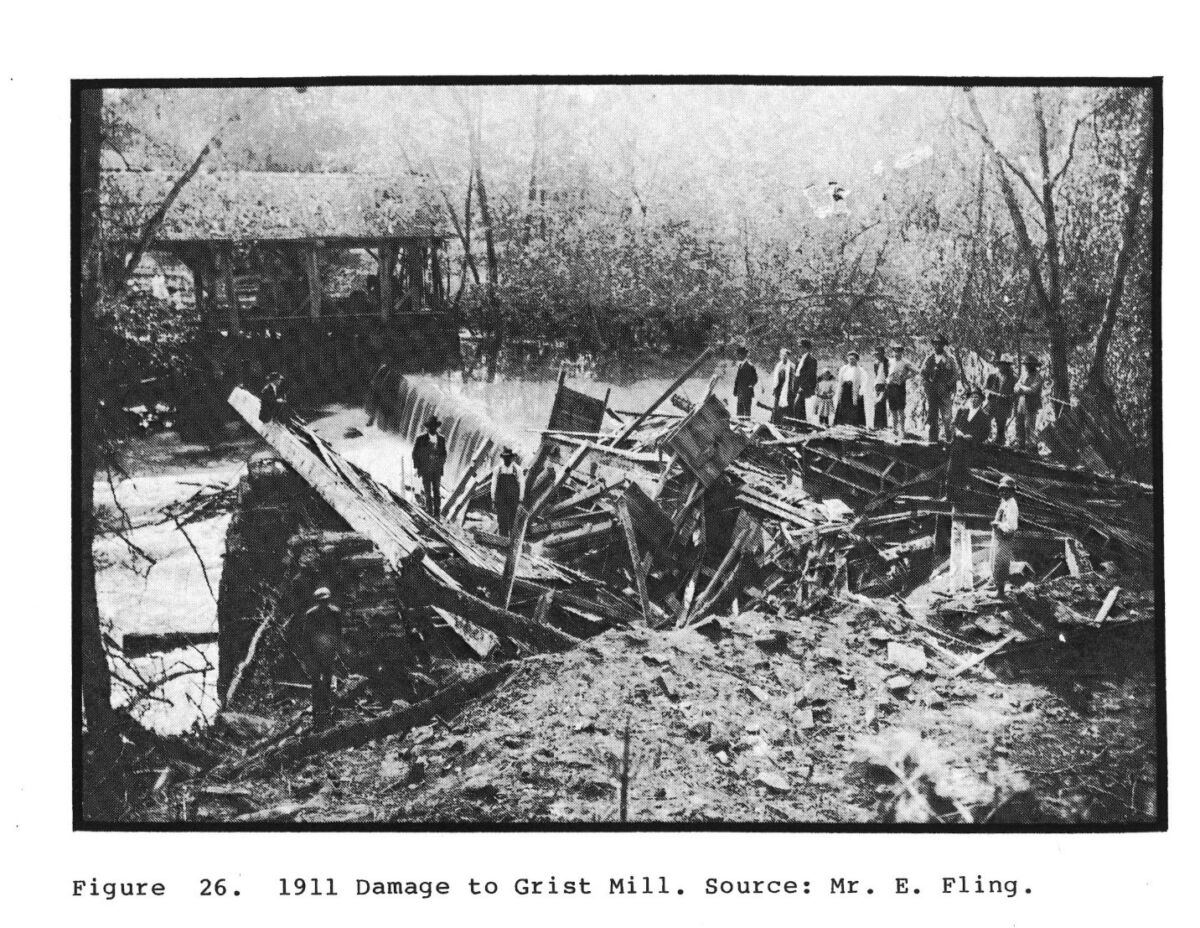

The first occurred around 1875, when Robert Young, Sr. hired a man named Haynes to remodel the old John Bird Mill. They installed modern water powered turbines to replace the old water wheel, and it was probably at this time that the saw mill was built on the north side of the creek. In 1911, Troup County road crews were blasting ditches adjacent to the mill. Somebody got a little too ambitious with the dynamite charges and the mill was blown to splinters. Within a year, with Troup County footing the bill, Robert Young, Jr. rebuilt the mill. It stood until 1971, when vandals burned it.

Wreckage of Young’s Mill following the 1911 explosion. Photo credit: Emmett Fling, The Meal Tastes Sweeter

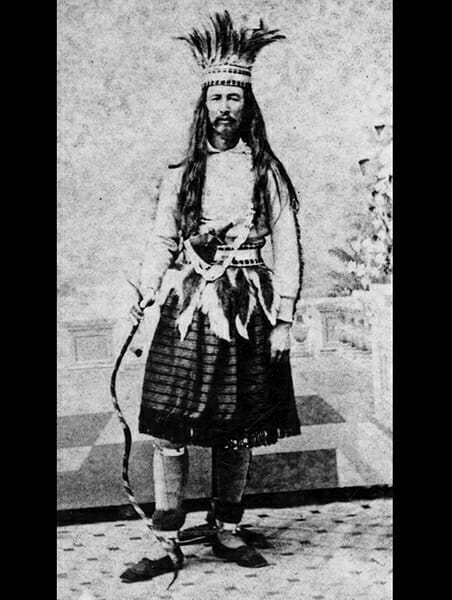

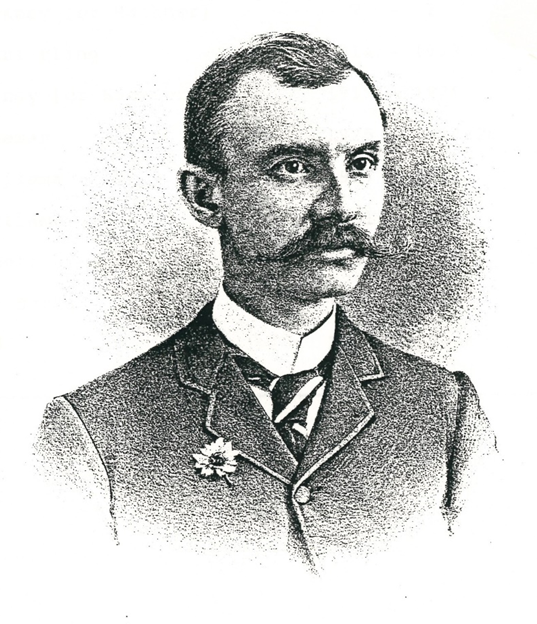

Born in 1863, Robert Madison Young, Jr. was part of that post-Civil War generation of entrepreneurs who capitalized on the South’s abundant natural resources and cheap labor to accumulate substantial wealth. At age fifteen, he lost his right arm in a threshing machine accident, but he went on to attend the University of Georgia and became a lawyer.

Robert Madison Young, Jr.

He was an insurance broker and railroad promoter, but his primary source of wealth was the land. In addition to his cotton and timber land in Georgia, his wife owned farm land in Missouri where they grew grain. In late summer, the entire family would relocate to Missouri where Young oversaw the harvest. As is often the case, Young’s interest in business and civic affairs led to politics. In 1888, he was elected Ordinary of Troup County. That’s equivalent to today’s Probate Judge. He later served in the Georgia Legislature.

It might have been purely philanthropic, or it might have been to court favor with clients and voters, but beginning in the 1880s, and continuing until his death in 1939, Robert Young, Jr. developed a public recreation facility near the mill on Beech Creek.

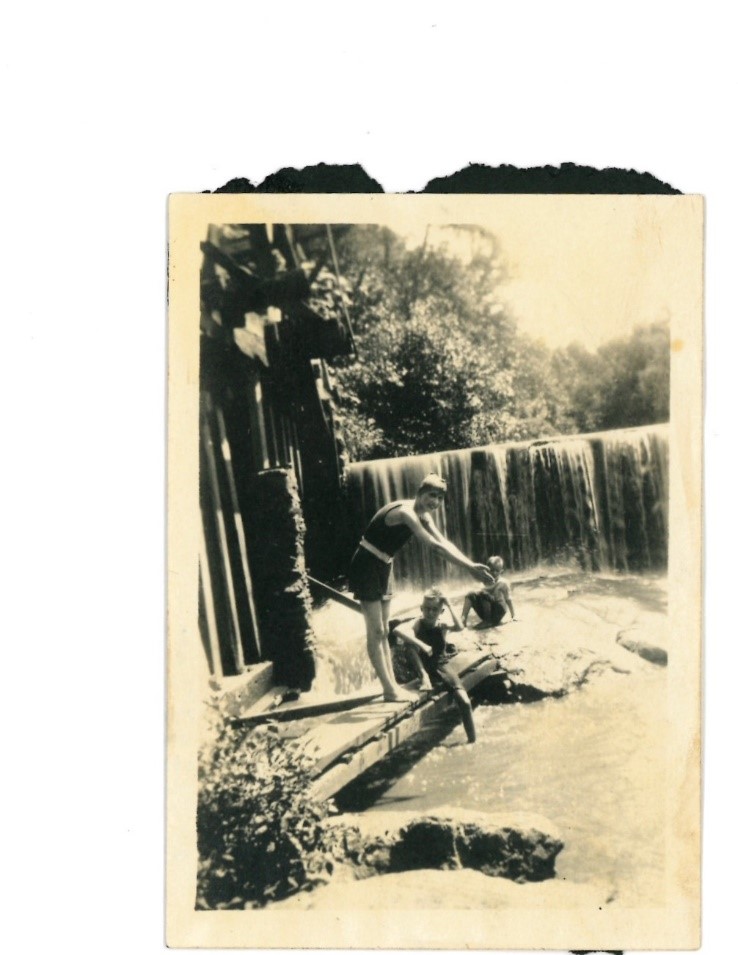

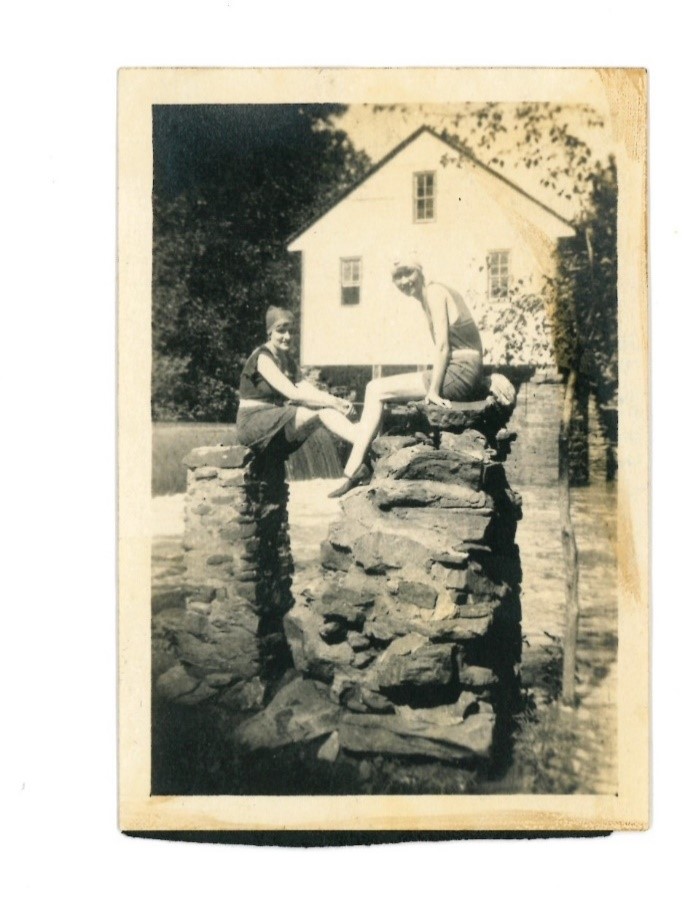

Louise Ware and Lurlene Bradshaw posed for snapshots during a 1921 visit to Young’s Mill and Lake Lahleet.

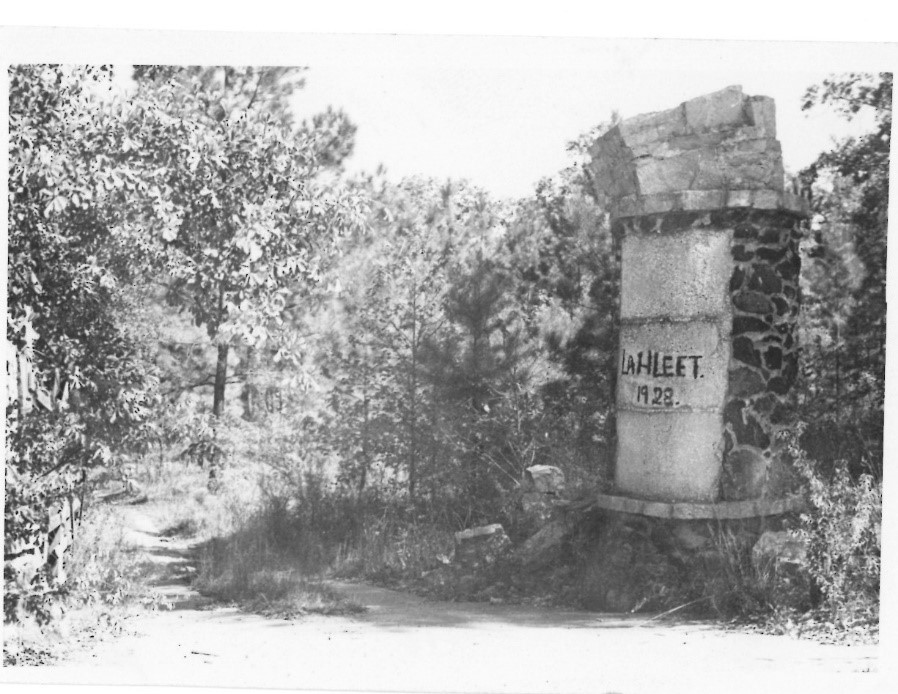

He called it Little Lake Lahleet. Inscribed on the stone entrance was, “For the boys and girls of today and tomorrow.”

Louise Ware and Lurlene Bradshaw posed for snapshots during a 1921 visit to Young’s Mill and Lake Lahleet.

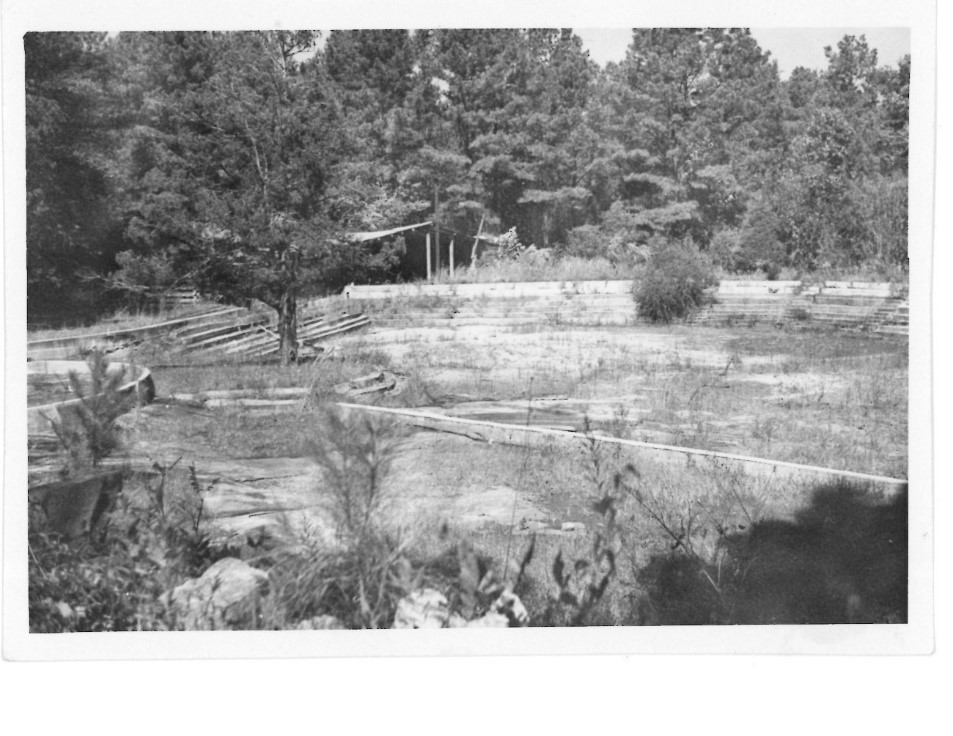

It was reminiscent of an old fashioned revival camp but with secular attractions. It featured a dance pavilion, cabins for overnight accommodation, and a rock lined swimming pool. It was a popular picnic spot for generations of LaGrange residents. In 1929, with his sons grown and on their own, Mr. Young decided to retire from business and devote his full attention to the mill and recreation area. It was then that he tore down the old Bird house and built the big Tudor style house where he and Lottie lived the remainder of their days. The LaGrange City directory for 1929, lists Robert M. Young, farmer and proprietor of Little Lake Lahleet.

LaGrange photographer, Stanley Hutchinson, recorded these images of the abandoned Lake Lahleet in 1946.

LaGrange photographer, Stanley Hutchinson, recorded these images of the abandoned Lake Lahleet in 1946.

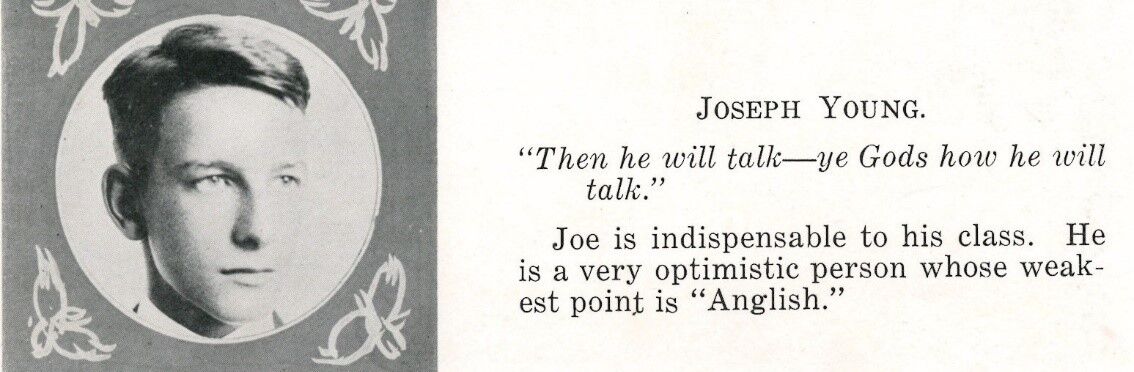

1922 Clarion, LaGrange High School

Joe was the youngest son of three born to Robert and Lottie Young. In a 1980 interview he reminisced about growing up on Hill Street in LaGrange. He related how he milked his father’s cows every morning and delivered the milk before going to school. He was proud that he was never tardy and over a nine-year period didn’t miss a day of school. He graduated from LaGrange High in 1922. In the Clarion, the LaGrange High yearbook, he states that his hobby is chickens and that his ambition is to “make tracks.”

That interest in poultry stuck with him all his life. There were always peacocks and turkeys and geese strutting around the lawns at Pineland. When he was in his seventies, he related a story about going to a cock fight up around Carrollton. — And, yes, cock fighting was illegal, even back then. — As he was leaving he noticed a little boy struggling to put a big croaker sack on back of a pickup truck. He offered to help and asked the boy what he had in the sack. The little fellow smiled up at him and said, “the losers.”

Joe Young’s Pineland Home; courtesy Georgia Sheriffs’ Youth Homes

Joe studied agriculture at Alabama Polytechnic Institute and after graduating in 1926, he went for further study at the University of Missouri where he was an assistant in the Poultry Science Department. In 1928, he returned to Troup County to help his father manage the farm. In the fall of that year, he started construction on a log cabin that would become the centerpiece of his beloved Pineland. A newspaper article published in May 1929, calls Joe the area’s most eligible bachelor, and describes as rustic on the outside but elegant on the inside, the log cabin he had just built on his family’s estate. Constructed from logs cut on the property, the cabin is two stories high with a basement and sleeping wing off the rear. The most impressive features are the massive quartz chimneys at either end of the great room. Mr. Joe insisted on burning only seasoned hickory in those fireplaces, and the logs had to be four feet long.

On July 23, 1930, at an improvised alter in front of one of those fireplaces, Joe Young married Wilma Wheeler Dunn, whom he had met in Missouri. We know little about her other than she was divorced with two children. In an interview conducted fifty years later, Mr. Joe remembered that his new mother-in-law, Nora Wheeler, was impressed with the huge trees along the drive that led to the house. She suggested they call the farm Pineland. The name persisted; the marriage didn’t. The thing I remember about that long drive, in addition to the big trees, was the hand lettered sign he put up. It read, ”Drive carefully, you might meet a fool.” Mrs. Helen, his second wife, whom he married in 1959, drove a big Chrysler, and there were so many, and such big potholes, on the road that she had to have it realigned about once a month. She, and others, constantly complained to Mr. Joe about the road. His reply was always the same, “Discourages company.”

As a reservist, Joe was called to active duty in World War II, and rose to the rank of Lieutenant Colonel in the Army Quartermaster Corps. His last assignment was in California, and when he retired from active duty in 1946, he left the west coast with a train car loaded with three Morgan horses and a small herd of jersey milk cows. He was returning to Pineland with boundless energy and ideas.

Always an innovative farmer, Joe Young, photographed in 1970, with County Extension Agent, Paul Patten, promotes clover as a forage crop.

One of his first moves was to refurbish the mill and get it running again. Indications are that he was less concerned with the mill’s profitability than he was with continuing the tradition of a working water mill. There seems to have been a good market for the meal in the LaGrange area, but Joe bristled at Food and Drug Administration requirements to add vitamins to the meal. Young’s Mill operated sporadically through most of the 1950s. In a 1989 interview, Helen Young stated that the mill closed for good in 1959, when her mother-in-law, Lottie Guinn Young, died.

Joe Young hosted trail rides and other field days at Pineland. Young is mounted on his favorite palomino, directly behind the child on the pony.

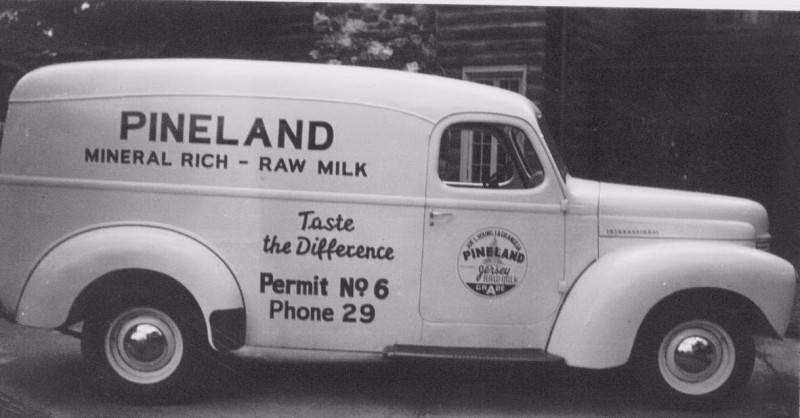

Pineland Dairy also failed to flourish. In 1952, citing difficulty finding competent help to run the dairy, Joe sold the jersey heard. His endeavors with angus beef cattle and Morgan horses were a different story. Morgan horse enthusiasts, to this day, seek out Pineland bloodlines. Mr. Joe favored palomino colored horses, and right up until his death, he was producing championship stock. The same was true for his black angus cattle. One of my last memories of Mr. Joe is bouncing over his pasture checking the cows. He stopped the truck and pointed out a big black bull. “That’s Cator of Wye,” he said, “and he weighs one ton.” In addition to the Pineland property, Mr. Joe had a big farm down around Perry, Georgia. Well into his seventies, he drove down there three times a week to check on things. He was an avid gardener all his life, and delighted in sharing giant turnips and other oddities he grew.

Now, all this sets the scene for what Joe Young felt he was losing to the dam project. It was twelve hundred acres of the best bottom land in the county, but more importantly it was a way of life. Joe Young was one of about nine hundred individuals who lost their property. Almost all, including my grandmother, viewed it as inevitable. Backers of the dam cleverly promoted it as economic progress. Most of the land owners saw it as a fight they could not win. My grandmother was accustomed to losing, picking up the pieces, and struggling on. Joe Young was used to getting his way; he was tenacious, and had the resources to fight.

At a meeting held at the General Tyler Hotel in West Point on November 24, 1958, promoters organized the Middle Chattahoochee River Development Association. The Corps of Engineers had scheduled their public hearing on the project for December 3rd, and dam proponents wanted to be sure they had their ducks in a row with the quasi-official organization. During the evening, business leaders and politicians representing towns from Atlanta to Columbus extolled the benefits of another dam on the Chattahoochee. As the proceedings were about to close someone at the head table indicated that the group had not heard from the “mayor of Young’s Mill.” After apologizing for intruding into what he had been led to believe was a public meeting, Young addressed the gathering.

Gentlemen, I am not in favor of your project. How many of you own property on the river? How many of you understand what the land means to some people? The land is my life. The dam you stand behind would put my land under water. I am one man, a little man. I want to ask: what rights do we little landowners have? You and the government have the right to condemn my land, to tell me how much you’ll pay me for it and then cover it up with water. Who speaks for the little man? Gentlemen, I realize the benefits which may come from the construction of a dam, but when you back up water over my property, you have taken away the only life I know – my land. I am not yet sold on your idea and I want somebody to sell me.

A contemporary newspaper article said a stunned silence befell the hall.

Mr. Joe’s impromptu rebuke impelled the dam promoters to broaden their effort and they packed the Corps of Engineers’ December 3rd meeting with over four hundred vociferous supporters of the dam. Only Joe Young, Guy Word, and Thomas Glass spoke in opposition to the dam. Over the next fifteen years, Joe Young, assumed the role of Troup County’s version of Don Quixote. Dam proponents ridiculed him for standing in the way of progress. Even his close friends and fellow land owners chided him for undertaking a hopeless fight. He sought news coverage to highlight the plight of those dispossessed by the dam. He negotiated with the Corps – Could they move the line to save his drive? Could they move the line to save an especially large specimen tree? Could they move the line to save his pump house? If he couldn’t beat the government, he could at least be a thorn in their side. He compared fighting the government to fighting a snake in a bush. “You just can’t get at them.” He rejected the price the government offered for his land. The final decree in Civil Action No. 1102, in the United States District Court, seized by condemnation about 1,200 acres of his land along Beech Creek and the Chattahoochee River. In all, the government purchased or condemned 56, 300 acres in 1050 individual land transactions. They paid $16,700,000, or about $300 an acre.

Despite his prediction, Fred Alewine lived to see the dam project completed, his house demolished, and most of his land inundated. He sold what was left to developers and bought a small place up near Hogansville. My grandma moved back to the mill village. The rich topsoil from her cornfields was used to construct the new bridge abutments on U.S. 27. Joe Young, embittered but resilient, continued in the role of country squire. Even with the loss of the mill site and all his bottom land he retained a couple of thousand acres. He was determined to find a way to keep the remains of Pineland intact. He had no children of his own and likely feared that members of his extended family would squander the estate after his death. As Mr. Joe’s health began to fail he confided to close friends that, as he put it, the buzzards were circling. On one occasion when relatives were visiting, Mrs. Helen put out a call that Joe had gone missing. His friends turned out to search the farm without success and were about to call out the bloodhounds and helicopters when my cousin called Mrs. Helen. He had found Mr. Joe and the Travelall parked at a remote deer hunters’ camp. “What are you doing way back here in the woods?” my cousin inquired.

“Them folks still at my house?” Mr. Joe turned the question. “You just go on, boy, and leave me alone.” My cousin complied. Joe Young died on February 8, 1986, and probably disappointed “them folks” by leaving Pineland to the Georgia Sheriffs Association to support a home for abused children – as the inscription at the old mill site reads — For the Boys and Girls of Today and Tomorrow.