By Thomas Daniel Knight and Randall Allen

Troup High Key Club member, Bruce Batchelor looks on as Dorothy McClendon, dressed in her “cemetery uniform,” clears a grave in the John Hill Cemetery at Long Cane. Key Club helped clean the cemetery as a service project in October, 1980.

(Troup County Archives)

Fair warning – This post will be a hodgepodge of reminiscing and nostalgia. Both Danny and Randy have some experience writing history articles, but neither has ever attempted to write a biography of a friend. Our goal is to recognize Mrs. McClendon for the contribution that she made toward preserving a significant part of Troup County’s history, the forgotten rural cemeteries. We trust that the anecdotes we relate here will introduce this remarkable lady to some of you. If you were privileged to know Dorothy McClendon, we encourage you to share your stories and memories. In either case, please be indulgent, as we ramble on, jumping from story to story, in a disjointed fashion so reminiscent of a conversation with Dorothy.

Dorothy Elizabeth Hopkins was born May 5, 1920, in what was then Campbell County, Georgia. She was the only child of Kaney Lawrence and Omie Dell Griswold Hopkins. During her childhood, the family lived in Atlanta, where her father was an insurance salesman, but home was always the area around Palmetto, Georgia, where her Hopkins ancestors settled in the 1820s. The modern Serenbe Community occupies land that was once the Hopkins farm. When Dorothy was a teenager, her father relocated to the West Point – Lanett area. She married Oran Harvard McClendon in 1942, and they had three children. Mr. McClendon died in 1975.

Mrs. McClendon’s involvement in her community extended far beyond charting lost cemeteries. Her enthusiasm earned her the honorary title of Mayor of Gabbettville. She was a member of Long Cane Methodist Church. In fact, the cemetery book was the result of her active support for the small congregation. She participated in the foster grandparent program. She never missed a DAR or UDC function, and she was the driving force behind establishing the West Central Georgia Genealogical Society, all while working full time as a registrar on the orthopedic floor at West Georgia Medical Center.

The cemetery project started simply enough. As a genealogist, Mrs. McClendon attempted to locate the grave of her ancestor, Joseph Deloach. She didn’t have much luck finding her own ancestor’s grave, but as word spread that she was searching for cemeteries in Troup County, people from as far away as Texas began to contact her asking for help. She realized that the old cemeteries were a valuable cultural resource and that they were severely threatened. In the preface to her book she wrote:

I knew how valuable cemetery information is to someone looking for a family member. Harmony, Long Cane, Bethel, and Pleasant Grove churches needed funds to build a parsonage, and we decided that the book project would be a way to raise funds. Miss Lillie (Lambert) and I started charting cemeteries in that area, and enjoyed it so much, the small project expanded. I couldn’t turn down looking up a new cemetery since we both enjoyed the challenge of finding new ones.

I remember so many small adventures: good muscadines at the Provident Cemetery; eating hot biscuits, tomato gravy, and cheese, early one Saturday with Pat Hogg and Randy Allen at the home of Sarah Starnes (my introduction to tomato gravy, and it was so good); spreading lunch with Betty Jones Jackson in her home converted from a church; sharing Miss Lillie’s cookies with Ornan Whatley; and seeing only one snake, and it was a little one.

Randy recalls:

Dorothy McClendon was probably the most engaging person I ever met. She drew people into her sphere with a combination of sincere interest in their stories and unbridled enthusiasm for the projects she promoted. I met her in late January, 1979. (The best time of year to search for cemeteries is mid-winter, when ticks and snakes and deer hunters aren’t an obstacle, and vegetation is sparse enough to allow you to spot telltale cedar trees and rock walls.) My mother called and informed me that she had met a very interesting lady at the beauty parlor, and she volunteered me to accompany this lady to visit some cemeteries in the southern part of the county. I walked into the country store where we had agreed to meet, and there stood an imposing figure, taller than average, dressed in a poplin shirt that bore a Coca Cola insignia, heavy trousers, and high-topped snake boots. “I’m Dorothy McClendon,” she said. “I brought you a ham sandwich for lunch, but you’ll have to earn it.” It was the first of many ham sandwiches and many wonderful days of rambling the back roads and woodlands of Troup County in search of elusive ancestors.

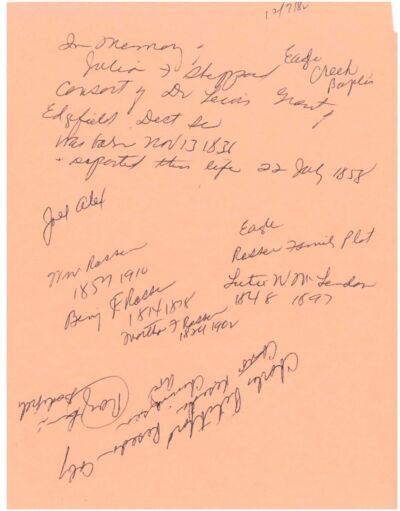

An example of Dorothy’s field notes

(Troup County Archives)Her cadre of volunteers included deer hunters who had stumbled across long forgotten graves, youngsters who were anxious to find the graves of their ancestors, and many, many, old timers who remembered visiting the cemeteries in their youth. I regret that I did not write down the tales they told. At this point, I can only remember bits and pieces. Boogie Freeman told us about the pest house at Abbotsford where typhoid patients went to die. My own ancestors perished in an epidemic around 1900, leaving four orphans to be reared by relatives. Bob Frank Floyd pointed to a cow in his pasture and said that she was a Mayflower descendant. His family had maintained the same bloodline of cattle for generations. They were descendants of the milk cow called Mayflower, who had walked along with the Floyds on their trek from North Carolina to their new home in Troup County. One of Mrs. McClendon’s informants was a notorious bootlegger who gave precise directions, “Follow this branch ‘til you come to my still. That graveyard is on top of the hill, about a hundred yards above the still.” We found the cemetery with no trouble, but we didn’t tarry. We were not always so successful. Mrs. Charlie Will Lane accompanied us on the search for a lone grave that was supposed to be located on the north side of McCosh’s Mill Road. It was bitterly cold and windy, the winter light was fading, and we were about to give up, when Mrs. Lane’s little feist dog, Precious, jumped a rabbit. Precious’s primal instincts kicked in and off she went, yipping behind the cottontail. Being country people, we knew the rabbit would eventually circle back. There was nothing to do but stand there, shivering in the gloaming, while Mrs. Charlie Will implored at the top of her lungs, “Pre – cious, come back, baby.” We all survived, but we never found the grave.

I got this story second hand, so I can’t vouch for its veracity. Dorothy was stopped at a country store with some of her volunteers enjoying their ham sandwiches when she saw a little boy throw a Coke can in the trash bin. With typical abruptness, “Here,” she said, “Don’t throw that can away. We’re collecting aluminum cans to put a new roof on the church.” She retrieved the can and with the heel of her heavy snake book, she demonstrated how to flatten it.

The little boy scampered off but soon returned with half a dozen more cans, proclaiming, “It’s gonna take a heap of cans to cover the roof on that church.” As the others began to chuckle at the boy’s naivete, Dorothy looked at the little fellow and said, “Yep, a whole heap of cans. Thank you so much.” Every time I drive by Long Cane Methodist Church I picture it covered in shiny aluminum cans.

Danny remembers some of his experiences with Dorothy:

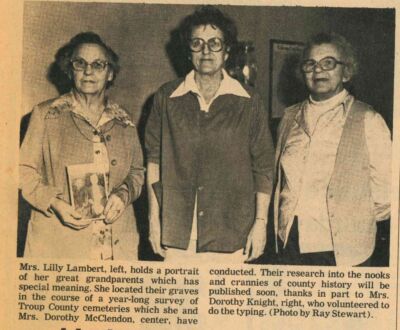

This article appeared in the LaGrange Daily News on February 1, 1979. More than ten years would elapse before the book was published, and Dorothy and her volunteers would log thousands of miles and man hours in the process.

Even though she’s been gone thirty years, she lives vividly in my memory. Tough on the exterior, she had a heart of gold.

When I was researching the Long Cane Community for a National History Day project in 1983, Mrs. McClendon shared her Long Cane Cemetery files with me. She soon began taking me to some of the more difficult to find cemeteries, on occasion with Mrs. Lillie Lambert, who was a lovely and remarkable lady, as well.

Many Friday afternoons, during the time I was in high school, she would pick me up at my house and we’d go to cemeteries. One Friday she picked me up for a trip to Rock Mills. Our house is about a tenth of a mile, or longer, off the road, and the driveway just sort of meanders through the pasture. It had been raining a lot that spring, and the grass was two to three feet tall in patches along the drive. As we were leaving my house I said something like, “I don’t know why Daddy hasn’t got out here and cut the grass.”

She looked at me in a classic Dorothy McClendon expression, and said, “What’s the matter with you? Can’t you push a lawnmower?”

So the next day I got out and cut the driveway!

One time we picked up Mr. Ornan Whatley (1898-1991). I think he was eighty-nine at that time and out plowing in his field with a plow pulled by a mule. He had on overalls. He stopped plowing, put the mule in the pasture, and got in the car. Mr. Whatley had an excellent memory, and as we drove around the western side of the county, he told us about growing up in the area. I was seventeen years old, and it was such a unique experience that details of that day are still imprinted in my memory.

Until you got to know Dorothy, her manner could seem a little abrupt. On another occasion, we were at Rock Mills looking for information on the Burke family and some graves at Wehadkee Church. We met a very old man, who was to help us locate the grave of his great grandmother. Dorothy asked him if he knew where she was buried, and he replied simply, “Yes.”

She was not easily satisfied with simple answers. “Well, where is the grave?”

He told her.

“How do you know that’s where she’s buried?”

“Well, I should know. I helped dig the grave in 1910.”

“Well, okay then. If you dug the grave, you ought to know.”I went to a lot of cemeteries with her between 1983 and 1988, sometimes to get inscriptions at new cemeteries she’d just heard of, and sometimes to go back and verify things. She took most of her cemetery notes on the back of blank forms that she had recycled from the hospital. Others were scribbled on legal pads or in spiral notebooks. All were shoved into a vinyl tote that she called her cemetery bag. Somewhere along the line, I suggested that she should publish the material. She explained that as far back as 1978, they had wanted to do a book, but for various reasons, the project never materialized. I guess I can attribute it to youthful enthusiasm, but I soon found myself organizing and typing her notes. I remember typing during my senior year in high school and my freshman year at Washington and Lee. In the spring and summer of 1989, I worked with Martha Anderson on the index. Eventually, with the aid of Troup County Historical Society and R.J. Taylor Foundation the book was published. My last communication from Dorothy came shortly before her death in December, 1993. I had returned to England to study. Dorothy called my mother and left a message for me. Mother, who knew that she was undergoing chemotherapy, commented that she sounded good. “Well,” she said, “You know, you can’t keep a good woman down.”

Not long after the cemetery book was published, the cancer that Mrs. McClendon had battled for several years recurred. With typical Dorothy McClendon pragmatism, she instructed her children and a few close friends to go from the cemetery following her funeral, straight to her home, box up all her records, and take them to Troup County Archives. She died in December 1993, and her wishes were fulfilled. For many years, researchers depended on “that quirky cemetery book” to find graves in Troup County. Mrs. McClendon was emphatic about recording the full inscription on tombstones, not just the birth and death dates. It is one of the lasting legacies of the book, as many of the older stones are now illegible, or nearly so. Taphonomy, the study of cemeteries, has become a pretty big subfield of academia, and the tombstone inscriptions have cultural value beyond the genealogical names and dates. The advent of digitization presented new opportunities for researchers. In recent years, Archives volunteer, Don Flynn, has donated hundreds of hours to update Mrs. McClendon’s work. Researchers can now find a grave with a few keystrokes on the computer*, but oh, what adventures they are missing!

*The Cemetery Database of TCA’s previous website is coming soon to the new site.