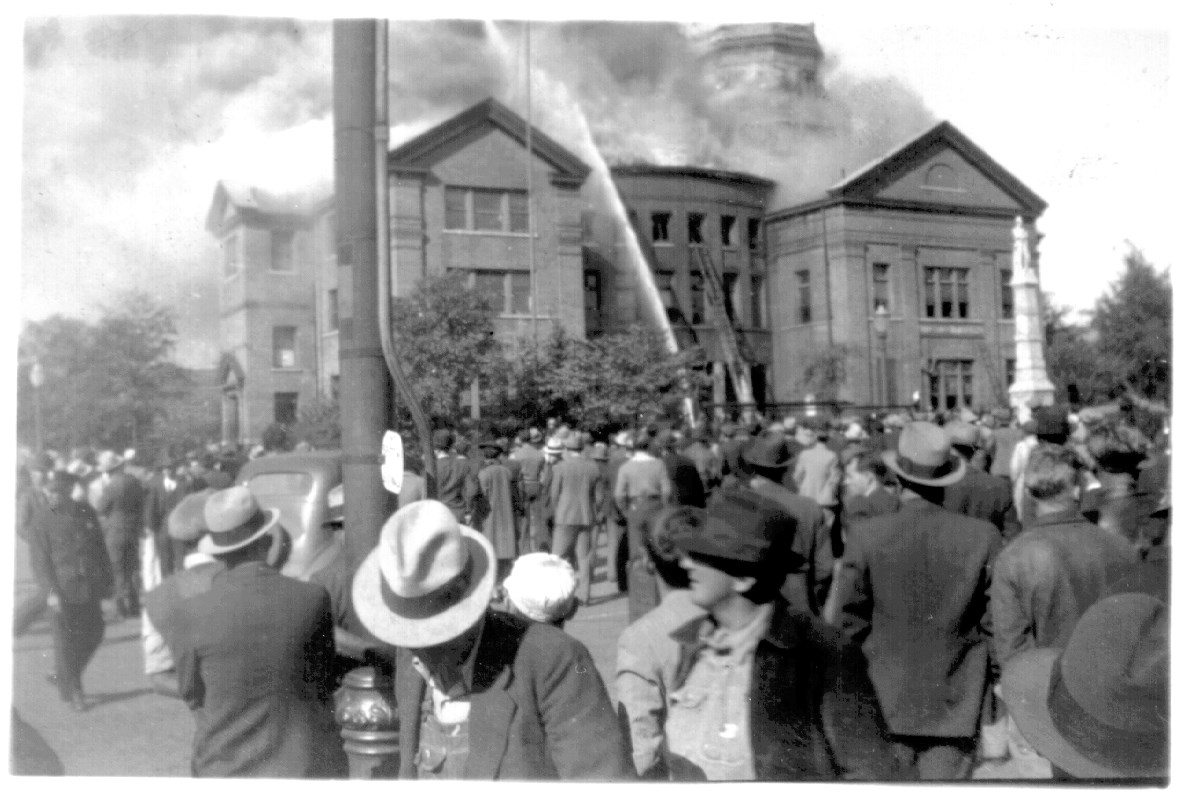

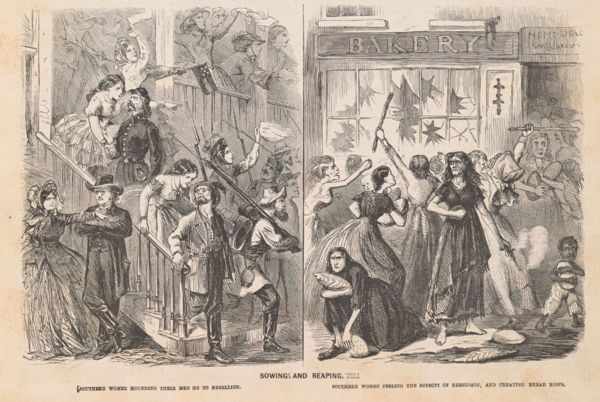

“Sowing and Reaping,” was printed in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper on May 23, 1863 in response to the bread riot in Richmond, VA. Protests-turned-riots occurred in a number of cities across the South, including Mobile, AL, Columbus, Macon, Atlanta, and Augusta. Image courtesy Library of Congress

The South of the early nineteenth century provokes thoughts of grand parlors filled with the

hoop skirts of genteel ladies and dining rooms laden with lavish feasts, while enslaved individuals

toiled in the fields nearby. Reality, though, was that those elegant parlors lit by glittering

chandeliers and chic meals created by French chefs were concentrated to the more established

regions of the South, along the coast, in cities like Charleston, Savannah, and New Orleans.

One did not have to travel far from major waterways or settled areas to find a very different

culinary world.

Troup County was established out of the Treaty of Washington, signed in 1826, in which

the Creek or Muscogee Nation sold the land to the United States Government. It was a poor

deal for the natives living on the land and created infighting amongst the Creek Confederacy.

Despite the removal of Native Americans, it was their foods that helped sustain the white

settlers that followed them. As settlers pushed inland from the easter seaboard, they brought

their foodways with them when they could, and they often only grudgingly adopted the foods

and customs of the native inhabitants. Corn, hardy vegetables, and native game were central

elements in the diets of those earliest pioneers to this area.

As late as 1840, large areas of Georgia, Alabama, and Mississippi had few or no white settlers.

On an overland trip from New Orleans to Charleston in the 1830s the traveler Thomas

Hamilton described the interior of Alabama and Georgia as “beyond the region of bread” by

which he meant bread made with wheat. In much of the remote South, breads not made from

cornmeal were a luxury enjoyed by few. Along Hamilton’s journey, his fare consisted of

“eggs, broiled venison, and cakes of Indian corn fried in some kind of oleaginous [oily] matter.”

Just outside of Columbus, Georgia, in 1832, Swedish traveler Card David Arfwedson was surprised to see that the centerpiece of his

hosts’ table was a bottle of whiskey, “of which both host and hostess partook in no measured quantity, before they tasted any of the dishes.” He recalled that a three-course meal of “pigs’ feet pickled in vinegar formed the first course; then followed bacon and molasses; and repast concluded with an abundance of milk and bread, which the landlord, to use his own expression, washed down with half a tumbler of whiskey.” Settlers produced food in response to the conditions of the land; thus, corn, salted and smoked pork, and quick-growing vegetables such as turnip greens became staples in the frontier diet. Pork and whiskey – both products of corn – were mainstays of the rural table. Dried corn kernels were not only ground into meal and eaten as bread, but it was distilled as whiskey and used as feed for hogs. Once distilled, whiskey was more portable and resistant to spoilage than corn.

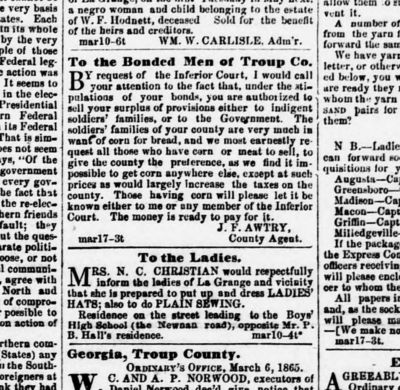

March 17, 1865 issue of the LaGrange Reporter in which the Troup County Inferior Court’s County Agent, J.F. Awtry posted a notice authorizing surplus provisions be sold to indigent soldiers’ families or to the Government.

Additionally, whiskey was the best substitute for potable drinking water, which could be difficult to find in remote regions of the inland South. Deep wells were costly and time consuming to drill, water from streams had to be lugged over terrain, and rivers could be muddy. Once supply lines were established with major

cities or routes of trade, settlers were quick to bring familiar foods to this “new”

region, but many native foods became familiar and even beloved staples among

white settlers. As the region developed through the antebellum years, corn, perhaps more than any other indigenous food, would come to define cuisine and culture across the South. The antebellum South was nothing if not agricultural. In fact, thanks to the vast farmlands, mild weather, and enslaved workforce, the antebellum South was one of the most productive agricultural regions in history. On the eve of the Civil War, as land-owning white Southerners contemplated their prospects in the conflict, few imagined their agricultural system would be anything but an asset. After all, Southern cotton was the fuel driving the Industrial Revolution; mills in the Northern United States and England relied upon it.

Southerners overestimated the power of cotton and underestimated the power

of food. Many Southerners believed that even without imports, the region’s farms

could produce enough food to ensure self-sufficiency for the duration of the war,

especially since the war was expected to be short. Those hopes were even shorter lived. The inadequacy of food production in the South became more and more

obvious as the Union blockade of Southern ports prevented almost all imports of

food and other materials. Periodicals like the Southern Cultivator encouraged readers to turn their fields from cotton to food, “Let it be understood at once, that the planter who cultivated cotton when there is such an urgent demand for food, is in effect giving aid and comfort to the enemy.” Too many were yoked to cotton production and many of those that might have made the switch had already left their fields to go fight. With crops increasingly dedicated to corn, and local officials increasingly impressing most of that crop to feed Confederate troops, many suffered food shortages. Poor white women whose husbands and other male family members left to fight for the Confederacy often became so desperate for food that they demanded help from city and state governments. The March 17, 1865 issue of the LaGrange

Reporter is filled with notices and updates regarding the Confederacy’s fate, but one notification is of particular interest. The Troup County Inferior Court’s County Agent, J. F. Awtry, posted “under stipulation of your bonds, you are authorized to sell your surplus of provisions either to indigent soldiers’ families, or to the Government. The solders’ families of your county are very much in want of corn for bread, and we most earnestly request all those who have corn or meat to sell, to give the county the preference, as we find it impossible to get corn anywhere else, except at such prices as would largely increase the taxes on the county.”

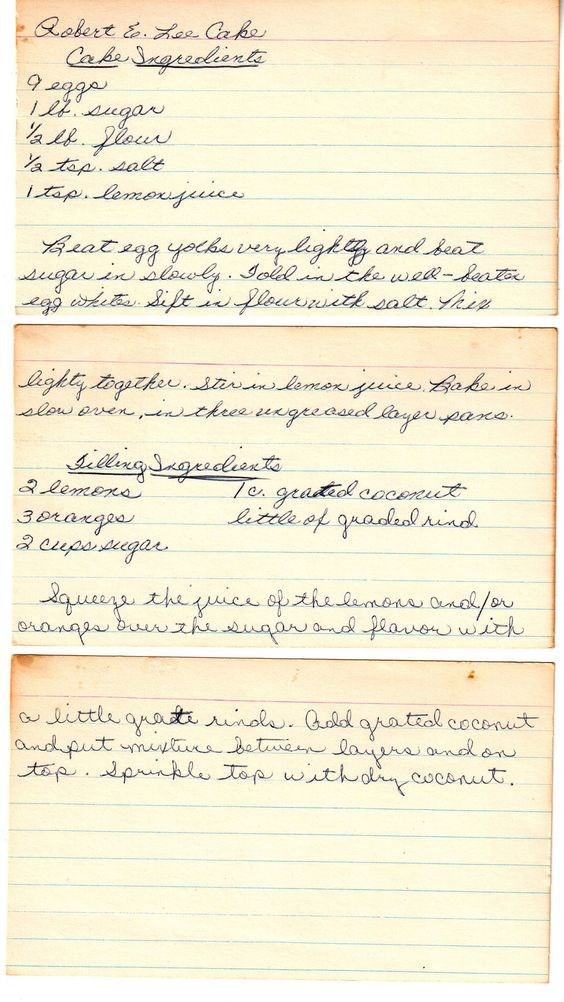

Recipe cards for a Robert E. Lee Cake. TCA Collections

In the fall of 1863, the Southern Watchman, another

periodical reported that a group of women near Columbus, Georgia, “claiming to be the wives of soldiers,” wrote to the governor requesting

food and threatening to take it by force if their demands were not met. As circumstances deteriorated from bad to unbearable, thousands of poor women across the south rioted for food. Even when they did not riot, they wrote to their husbands at war, begging them to return to the farm to tend fields. The war took a devastating toll on African Americans in the South, too. Hunger, exposure, and displacement contributed to the staggering rates of sickness and death. While no Southerner went unaffected by the war, money and race created gross differences in the ways Southerners experienced it, insulating some from true want while exposing many others to harsh deprivations and suffering. This was especially true among the soldiers. After farm animals were consumed or had become casualties of war themselves, the troops turned to mules, horses, and eventually rats. Many commented on the quality of these novel sources of protein, one writing, that mule was “of a darker color than beef, of a finer grain, quite tender and juicy.” Ultimately, the South’s inability to produce adequate food and move the food where it was needed, directly contributed to its defeat. Even more than the outcome of the war, though, was romanticized memories of it, that profoundly shaped Southern culture and cuisine. When looking closely at Southern foods, it becomes apparent that many originate from nineteenth-century methods of preservation. Jams, vinegars, pickles, and smoked meats were all ways of extending the life of perishable foods. These methods, however, were not unique to the South; they are the same flavors that would have been

found on a Northern table of the 1860s. For example, the mess of limp collards or green beans boiled down to a savory heap with salt pork,

which today is thought of as a uniquely Southerndish, was common across the nation because of a belief that vegetables needed to be long cooked to ensure digestibility. Even before the war was over, recipes begin to appear memorializing prewar cooking styles and honoring Confederate officers, such as Robert E. Lee Cake, an orange cake believed to be a favorite of the General’s. It is the post-war celebration of the “Old South” that results in Southern cuisine continuing nineteenth-century cooking techniques, and the tastes and textures that resulted in those methods, in a way that Northern cuisine did not. So, many of the flavors we associate as Southern today, from the bite of vinegary peppers to the sticky sweetness of fruit jams and the saltiness of sausage, are really more the flavors of preservation than regionality. — Shannon Gavin Johnson