This flower and scrap are part of the scrapbook of Ellen Rebecca Pattillo Callaway. TCA Collec-tions, Accessions #MS-107.

Troup County Archives holds dozens of scrapbooks ranging from the Victorian Era to modern day. Each one is unique, yet they share common elements. By definition, they are bound albums filled with paper ephemera. That’s academic speak meaning that someone took the time to clip, collect, and paste together bits and pieces that held sentimental or aesthetic value. Newer scrapbooks in TCA collections usually follow a specific theme – club activities, for example. Earlier ones tend to be more fanciful. One researcher describes them as, “a labyrinth of memories puzzling to everyone except the owner.”

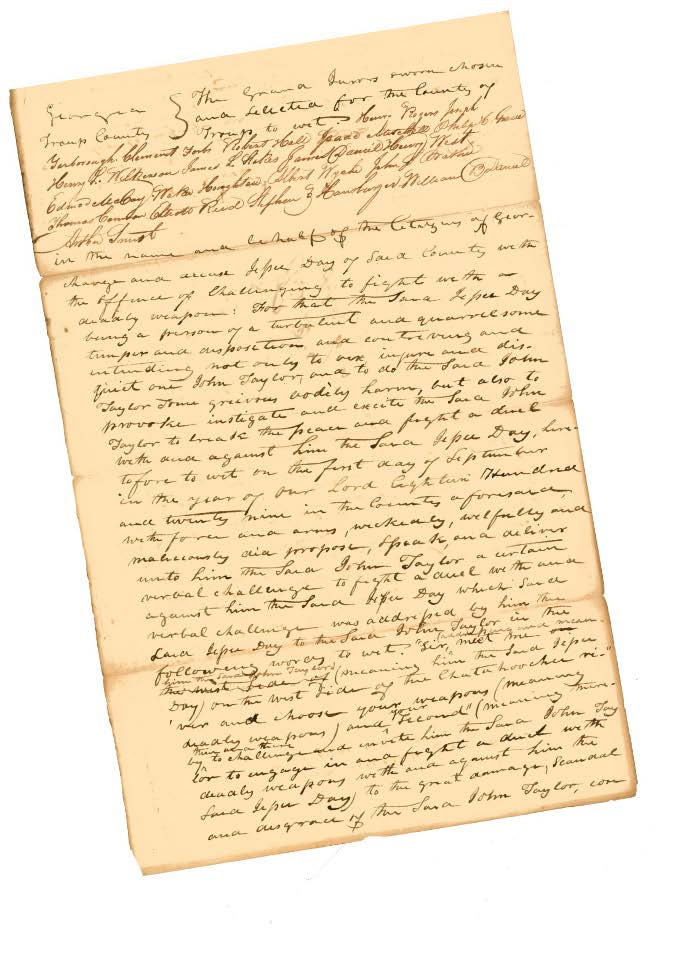

Scrapbooks are an invaluable window into bygone society. Broader in scope than diaries or journals, which have been around much longer, scrapbooks reflect a slice of our culture through literary excerpts, news clippings, calling cards, and even photographs. As early as the Renaissance period (fourteenth to seventeenth centuries), literate people kept what was called a commonplace book in which they recorded vital information. By the eighteenth century, people began pasting mementoes into their commonplace books. In the early nineteenth century, family Bibles became repositories for keep-sakes and important documents. The advent of inexpensive disposable paper and mechanical printing spurred the popularity of scrapbooks. The Victorians, with their penchant for embellishment, created our modern concept of scrapbooks.

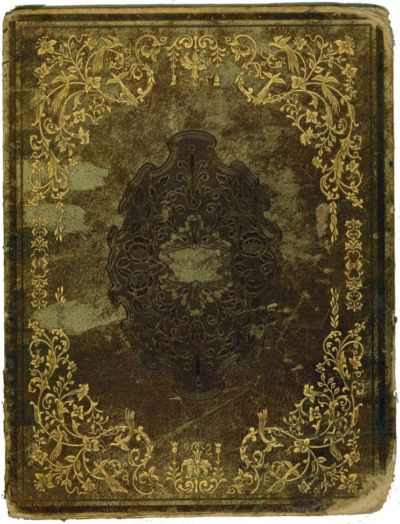

Mary Charles Evans Curtright kept this tooled leather album from 1851 to 1905. TCA Collections. Accessions #MS– 019.

These decorative albums were composed of “scraps,” thus the name, which were sometimes arranged quite artistically. Some albums were made with elaborately tooled leather covers, engraved clasps, and brass locks. Scrapbooks became indispensable as a method of teaching children both at home and Sunday school. Women’s magazines of the era suggested scrapbooking as an essential “rainy-day occupation” for children and included a list of materials for mothers to keep on hand for such days.

The Whopper Scrap Book is an example of the commercially produced scrapbooks that became popular. This example is one of the many in the Nix-Price Collection at TCA. Accessions #MS-004.

The development of the industrial printing press in the early 1800s made the mass production of printed materials possible. Samuel Clemens, also known as Mark Twain, even got on board. A life-long creator and keeper of scrapbooks, he always traveled with them, filling them with souvenirs, pictures, and articles about his books and performances. In 1872, he patented his “self-pasting” scrapbook, and by 1901, at least fifty-seven varieties of his scrapbooks were available commercially. It would be his only invention that ever made money.

Excerpts from three such examples in our collections are featured on these pages. Ellen Rebecca Pattillo Callaway toured the world after her husband, Samuel Pope Callaway, died. She wrote lengthy articles home to the local paper and kept many interesting items from her travels in her book. Caroline E. Gay, Carrie Nix Nooner, and other ladies of the Nix-Price family compiled numerous scrapbooks dating from 1920 to 1960

that feature local newspaper clippings. Finally, the lovely tooled leather album was kept by Mary Charles Evans Curtright between 1851 and 1905.

From a conservation standpoint, scrapbooks are a bit problematic. Until recent years, scrapbook makers ignored just about every principle of archival preservation. Newsprint and glue are anathema to conservators. Early twentieth-century scrapbooks, in particular, are made from highly degradable materials so that the slightest disturbance brings a shower of brittle newsprint. Even modern scrapbooks tend to be behemoth volumes that never fit conveniently onto our shelves. These factors – the fragile condition and the bulky odd sizes – make us reluctant to handle the scrapbooks.

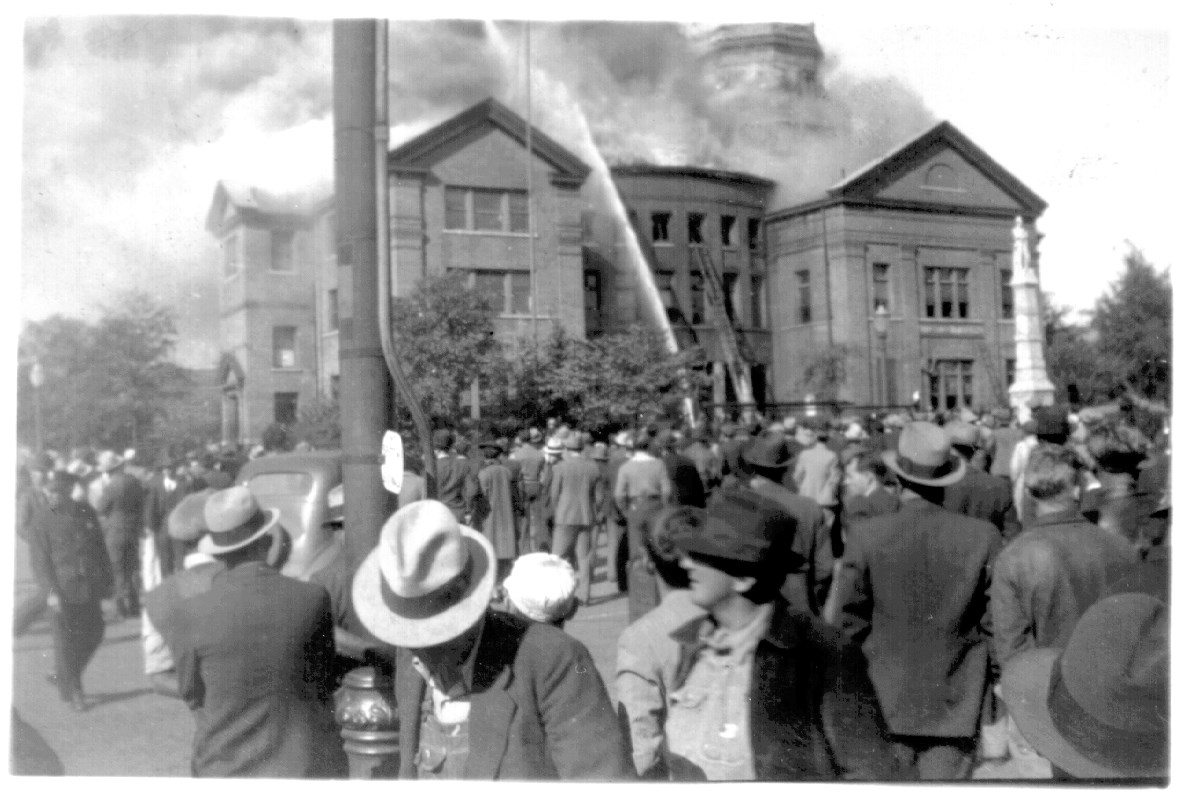

That situation creates a twofold dilemma. Our scrapbooks are a goldmine of historical information. You are probably aware that a fire destroyed almost all of LaGrange’s early newspapers. Articles gleaned from scrapbooks often fill gaps in the record. Equally significant, even if you are not an avid genealogist or historian in search of arcane data, it’s just plain fun to sit and leaf through one of the big ornate books, perhaps catching a glimpse of the original owner’s musings.

This little Dutch shoe is actual size, and was pasted into the scrapbook of Ellen Rebecca Pattillo Callaway. TCA Collections, Accessions #MS-107.

If you have a little time to spare, we invite you to don one of our lab coats and pull on cotton gloves. We’ll teach you how to encapsulate, interleave, index, and scan these valuable resources to make them fully accessible.

— Randall Allen